Conducting qualitative research at scale

500 hours.

That's how much time our qualitative research team saved during a recent project, thanks to our new AI-powered thematic coding tool.

In another recent blog post, we discussed the importance and richness of qualitative research, which typically involves collecting data from participants through key informant interviews or focus groups discussions. Unlike quantitative surveys, qualitative discussions capture nuance, and can often shed light on why or how something happens.

The economics of qualitative research

Given the value of qualitative research, we at Laterite would love to do more of it. The challenge, however, is scale. Conducting qualitative research at the same scale as a quantitative survey is time- and cost-prohibitive. It involves painstaking manual work to record, transcribe, translate, code, and synthesize large amounts of text data.

Recent advancements in AI technology are changing the economics of qualitative research. As we shared in our other post, the process of transcription and translation has been simplified with new tools. However, there's another extremely time-consuming step – thematic coding of transcripts. This is where AI in qualitative research has the potential to make a big difference.

Thematic coding involves reading transcripts from interviews and tagging the text with relevant themes (or codes) being discussed. It's usually done using software like MAXQDA, NVivo, or ATLAS.ti. Coding a single 90-minute focus group discussion transcript can take up to three hours. It's a manual and time-intensive process that does not scale easily.

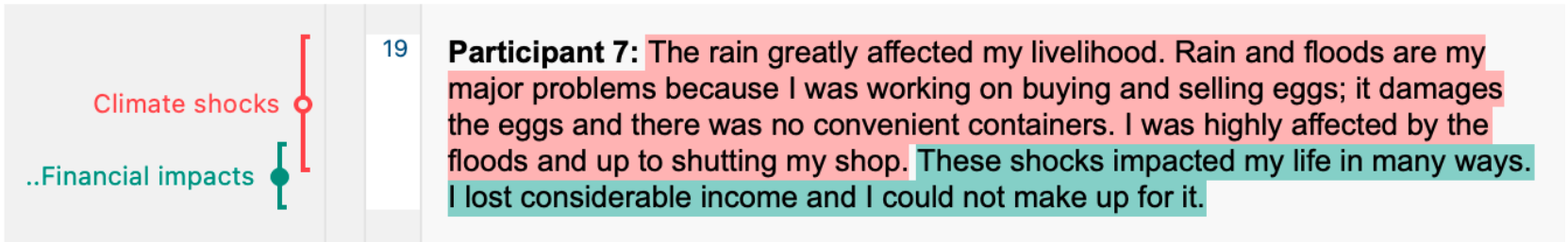

Example: Text from an interview transcript, coded with two themes in MAXQDA

Example: Text from an interview transcript, coded with two themes in MAXQDA

Conducting thematic coding at scale

In a recent project in Ethiopia, our research team faced a steep challenge: a qualitative sample of 342 focus group discussions and key informant interviews – representing 500 hours of conversation. Reading every line and coding it for themes in MAXQDA would take our small team an entire month of work – time we simply didn't have.

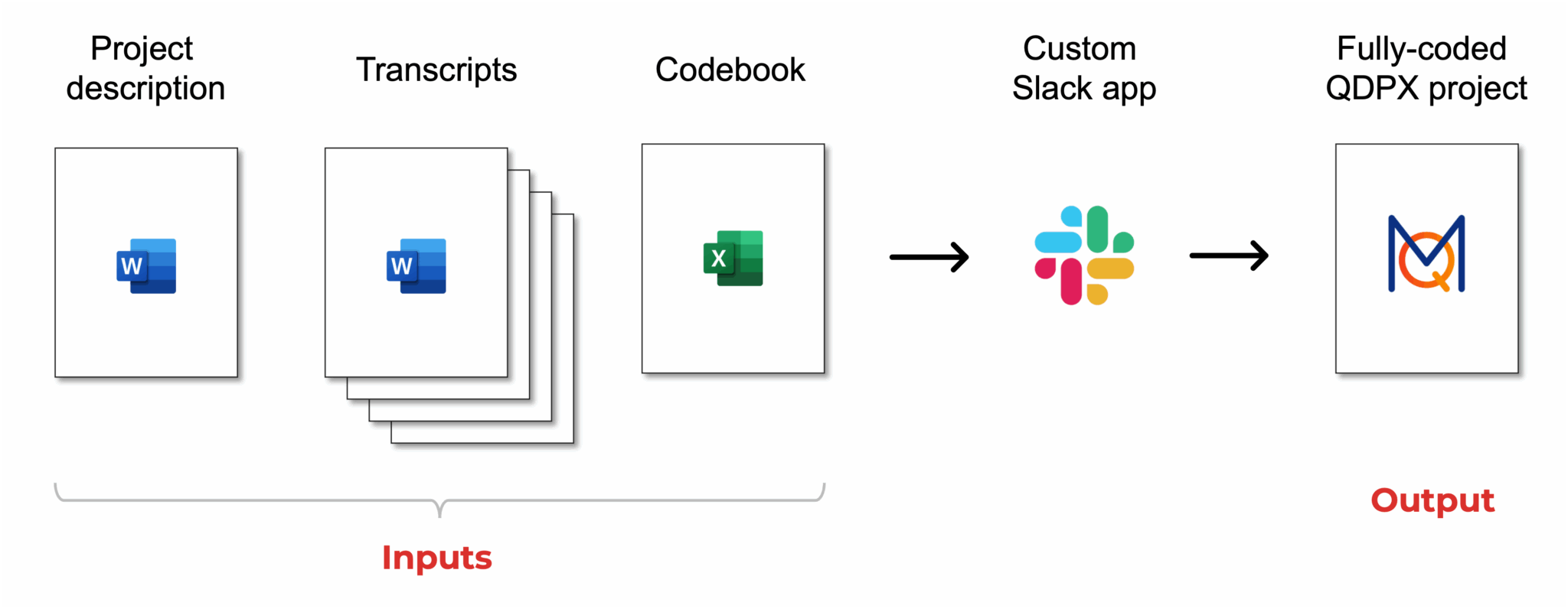

An in-house solution came just in time to meet this challenge. Laterite's Analytics team built a custom AI-powered application that reads interview transcripts and codes them for relevant themes, exporting a full MAXQDA, NVivo, or ATLAS.ti project. The app is accessible directly through Slack, and takes three inputs:

- A short description of the research objectives (Word document)

- A batch of anonymized transcripts (Word documents) to be coded by the system

- A “codebook” defining the themes that the system should identify and code in the text

How does it work?

Our application first processes the input documents, automatically identifying speaker labels (e.g., Participant 1; Moderator) in the transcript text. It assigns an ID to each speaker turn and splits the transcript into smaller chunks.

The codebook of themes is converted into a structured JSON format with nested codes (e.g., primary, secondary levels). The app then runs a series of repeated calls to an LLM API (e.g., OpenAI or Gemini), with specific instructions in a prompt on how to code individual text chunks.

The LLM gets access to:

- The entire codebook with detailed definitions of each code

- The research context outlining objectives, methodology, and key terminology

- The full transcript

- The specific text segment to be coded

The application then produces a file ready for review by our research team. Everything is packed into a QDPX project, an open standard file format readable by MAXQDA or NVivo. By linking our application directly to these tools, our researchers gain more time for analysis and synthesis, rather than tedious coding.

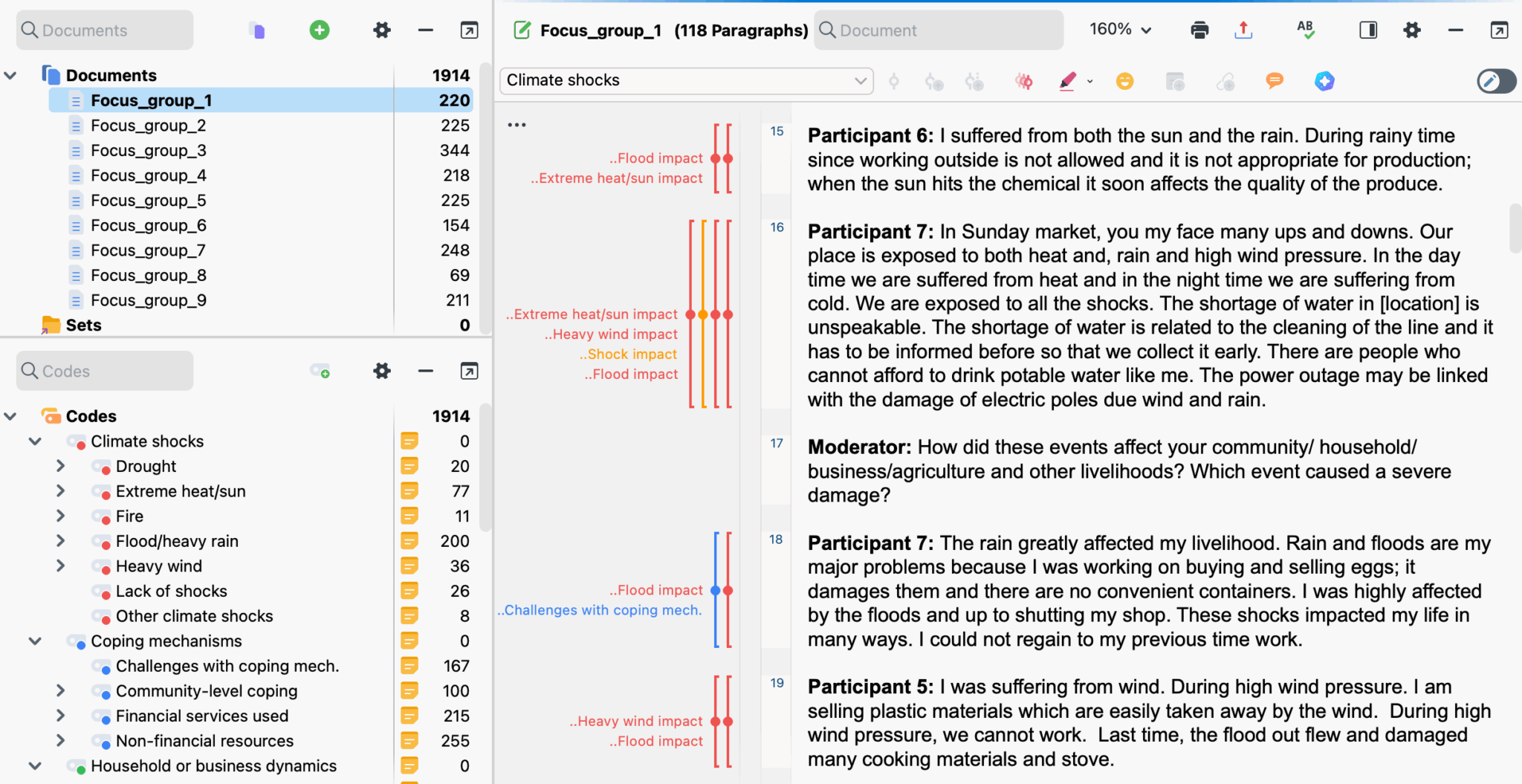

Figure: The final output – a fully-coded MAXQDA project

Figure: The final output – a fully-coded MAXQDA project

Measuring quality and mitigating risks

Two of the biggest challenges in this work were ensuring the AI outputs met Laterite's rigorous quality standards and addressing valid skepticism about using AI for qualitative work. Concerns about hallucinations, bias, missed insights, and a lack of human oversight were central to our process.

We built a system where the research team remains in control. The AI's role is limited to thematic coding, while humans manage the codebook structure, summarization, and interpretation. We also had our team manually code 140 of the 342 transcripts, which helped:

- Uncover issues with the codebook or transcripts before AI processing

- Ensure diverse representation (e.g., gender, region, interview type) in human coding to help avoid bias or mitigate the risk of missed insights

- Provide a comparison group to evaluate AI performance and serve as examples

We measured the AI's performance using inter-coder reliability (ICR), a common method for comparing the coding consistency among qualitative researchers. ICR is calculated using Cohen's Kappa statistic, with ranges from −1 to +1, with scores closer to 1 indicating greater agreement. Having a benchmark like ICR was essential to measure the quality of AI outputs in comparison to the human team, and to run experiments (e.g., different models, chunking) while tracking improvements. Our goal was to achieve an ICR comparable to human-to-human coding.

The results were impressive: our application coded 203 transcripts (about 250 hours of dialogue) in just two hours, compared to roughly 500 hours of human work.

Our tests suggest our system performed as good or better than the average human coder on this particular project. Through testing and tweaking, the ICR scores improved over time, eventually achieving our goal. Our best performing model at the time of the project was GPT-4.1, using a chunked input approach, and a curated set of human-coded examples in the prompts. This model achieved an ICR score of 0.55, slightly higher than the human-to-human average of 0.52. This approach demonstrates how AI in qualitative research can help overcome scale limitations while preserving methodological rigor.

Opportunities and reflections

There's still more work to do to refine and improve our application. One area we're keen to explore is bias in AI coding. LLMs are black boxes, and it's difficult to fully understand their decisions. To improve transparency, our system requires the AI to explain every coding decision so researchers can review it.

Still, we continue to ask important questions:

- Does the AI systematically favor certain codes?

- Does it interpret transcripts differently based on gender or language?

- How do translations influence meaning and coding?

At Laterite, we're cautious optimists about what these new technologies mean for research. There's rightful fear and criticism that this type of automation will render some research jobs obsolete, de-humanize findings, or lead to bias in results. All of these concerns are legitimate and should be carefully considered. However, we also can't ignore the tremendous potential these tools have to uncover richer insights in a fraction of the time and for a fraction of the cost. These tools let us do more research, hire more enumerators, collect more data, and answer bigger questions.

Imagine scaling qualitative work to the size of a household survey – thousands of voices, not dozens.

Our job as researchers doesn't change: we still listen closely, think critically, and produce useful evidence. The difference now is we can do it at scale.

This blog is written by John DiGiacomo, Director of Analytics at Laterite.